One hundred years ago, this week -

July 7, 1911, to be exact - an American man named Hiram Bingham found the ruins of an ancient ceremonial city, mostly overgrown with Peruvian jungle. Some indigenous families were living on the site, tending small subsistence farms. Despite the fact that local people had always known about the ruins, and despite the fact that the clues of other explorers and many indigenous people enabled his route, Bingham claimed to "discover" these ruins. Those ruins are now one of the world's most famous and most remarkable places: Machu Picchu.

Over the next few years, Bingham would bring Machu Picchu to the attention of the larger world. He would uncover other nearby Incan ruins and open the ancient paths between them, now known as the

Inca Trail. He would also violate an agreement he made with the Peruvian government, and illegally excavate, remove and steal ancient artifacts from those sites, including the remains of Incan people - the ancestors of people forced to work there.

As many of you know, I have an enduring fascination with both modern and ancient Peru. In 2006, Allan and I spent three weeks

traveling through that country. It was a trip I had wanted to make all my life, and a gift to ourselves after emigrating to Canada.

I've just finished reading

Cradle of Gold: The Story of Hiram Bingham, a Real-life Indiana Jones and the Search for Machu Picchu, by Christopher Heaney. Leaving aside the ridiculous subtitle, this book tells many intertwined stories.

Cradle of Gold is a biography of Bingham and the story of his Peruvian expeditions, with the surrounding historical context. That supposedly heroic tale is intertwined with a much older story, one that is truly heroic and tragic: the final Incan resistance to the Spanish invasion. The book also analyzes the struggle between modern Peru and Yale University over the the tens of thousands of artifacts that Bingham stole from Machu Picchu and other Incan sites, that Yale refuses to return. In addition, and more briefly, the author writes about his deeply felt personal connection to these subjects.

Heaney has written an ambitious book that clearly represents an enormous amount of research. He succeeds in all his stories, but of course not all readers will be equally interested in each threads. I have little interest in biography, and when I do read a biography, it's either to study history (like

Taylor Branch's monumental history of the US civil rights movement, framed by a biography of Martin Luther King), or to learn about a person whose life and contributions move me. I found myself distinctly uninterested in Bingham's personal story, and the story of the search for the Incan "lost cities" was written in more detail than I needed. But if you enjoy those kinds of tales, this is a good one.

The final chapters - on the case against Yale and the author's personal story - were, for me, the best parts of the book. Unfortunately, this was also the briefest part, and left me wanting to learn more.

* * * *

In the book's introduction, Heaney summarizes the Peru vs Yale fight this way.

In 2008, Peru sued Yale for the return of the artifacts and human remains that Bingham excavated from Machu Picchu. Peru claimed it had loaned Yale the collection of silver jewelry, ceramic jars, potsherds, skulls and bones and was now demanding its return. Yale called Peru's claim "stale and meritless" and asserted that now it owned the collection. Peru said Yale had 46,000 pieces; Yale said it had 5,415. Between these two distant poles, I have attempted to find the truth.

I interpreted this to mean that the author believed there is some middle ground, some compromise, between Peru's position and Yale's. I was wary and skeptical of how Heaney might justify a position.

I was relieved to be wrong. Heaney understands and beautifully articulates why Yale must return Peru's stolen history.

For years, Peruvian archaeologists grimaced while North American colleagues shook their head at the country's struggle to protect its culture. It was a patronizing argument that ignored progress: Peru's cultural institutions had moved forward in leaps and bounds since Bingham's era. More importantly, the executive orders [through which Peru loaned some artifacts to Yale] were proof that in the 1910s Peru did care about its history. The early negotiations over Machu Picchu's artifacts and Bingham's evasions were revelatory, and Peru was legitimately outraged that Yale denied their relevance.

Yale was surprised to learn that the third party in Bingham's later expeditions felt similarly. The National Geographic Society also wanted the artifacts' return. Its vice president, Terry Garcia, reviewed the society's documentation and felt there was "no question" that Machu Picchu's artifacts belonged to Peru. National Geographic attempted to broker a deal, but the university was uninterested. The society was shocked. "It's so patronizing of them to suggest that you can't return these objects to Peru because they can't take care of them - that a country like Peru doesn't have competent archaeologists or museums," National Geographic's vice president told the New York Times in 2007. "Maybe if you were a colonial power in the [nineteenth] century you could rationalize that statement. I don't see how you could make it today."

Much more than pottery and jewelry is at stake - although that must be returned, too. Bingham illegally removed the remains of 174 human beings from burial sites, people "whose ancestors now walk the streets of Cuzco and Lima". The Native American Grave Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) requires US museums to return human remains and spiritual artifacts to their living indigenous heirs. That law applies only to US tribes, but it sets a precedent, which was followed when, for example, the Smithsonian returned mummies to Cuzco.

The symbolism in the Yale case is deepened by the fact that the human remains are from Machu Picchu, the royal estate of Pachacutec - either one of the great indigenous leaders of Andean history or one of its great imperialists. Pachacutec's mummy is long gone, but the fact that the bodies and artifacts of the men and women who attended him are at Yale remains deeply unsettling. In May 2006, 1,200 residents of the town beneath Machu Picchu rode the train to Cuzco to demonstrate and call for the return of the Machu Picchu artifacts to their home. "What if Peru had George Washington's things?" the director of the Instituto Nacional de Cultura in Cuzco asked the year before. "We would have to return them. They would mean something to the United States, not Peru."

Heaney expresses more sympathy to Yale's position than I can muster, as he grew up around Yale's Peabody Museum, and he idolized Bingham. (Despite that, he does not present a sanitized or idealized version of Bingham; through his research, Heaney had to "grapple with Bingham's dark side," as he puts it.) Heaney describes a more recent visit to the Peabody, where a few dusty pieces from Cuzco are badly displayed, creating "the false impression that all Yale has are ceramics".

Leaving the Peabody, I feel torn. I do not believe the claims of major museums that if they send back one artifact, they will set a precedent by which all the world's art and artifacts will fly back to their creators' descendants. But I also believe there is some value in the international study and display of artifacts as examples of the world's diversity of art and culture. I grew up immersed in Peruvian, Oceanic, and African art and artifacts in the museums of New York. They filled me with wonder and sympathy. They made me want to travel. I want my future children to feel the same.

This really irked me. Privileged North American children can be filled with wonder and the desire to travel, at the price of another country's own heritage? Sure, it's more convenient

for the author if artifacts stay in New Haven or New York!

But Heaney redeems himself by showing that he is merely acknowledging these selfish feelings, not suggesting policy should be based on them.

I draw the line, however, when a loaned collection becomes a trophy, and includes human remains. I believe that Yale University should return to Peru the skulls, bones, and artifacts that Hiram Bingham excavated and exported from Machu Picchu and other sites as soon as possible without conditions. Peru does not deny the importance of Yale's curatorship of the collection, nor how it has deepened interest in Peru. Instead, its representatives call for their return because they believe it is historically, ethically, and legally right. . . . The fact that these are not just artifacts, but the skulls, bones, and funerary remains of Peru's pre-Columbian dead, makes Yale's intransigence doubly incredible. It is indeed problematic when a country's government, like Peru's, claims to represent a historically marginalized indigenous group — but that should be a problem worked out between the government of Peru and its indigenous majority, not Peru and Yale. These are not Greek sculptures on display in Yale's art gallery, planting the seeds of a hundred new artists — these are the skulls and bones and possessions of people who once struggled, danced, and buried family members of their own. . . . If, at their core, history and archaeology are our attempts to understand and respect the lives of the past on their own terms, then the respectful treatment of human remains is the litmus test of whether our practices are civilized or cruel. Yale's possession of Machu Picchu's dead not only lends an unattractive colonial tinge to the university but also shows how Yale refuses to recognize the expedition's place in the hemisphere's history of exploitation.

* * * *

Bingham's expeditions take place against a backdrop of US imperialism; deep, well-justified suspicion and distrust by South Americans of North American intentions and, often, their own government's desire to profit from US imperialism; indigenous forced labour, slavery and repression - and resistance; and an American and European public fascinated by heroic adventures. One interesting thread running through

Crater of Gold is the historically contradictory attitudes of white Americans towards indigenous people. It's a perfect illustration of the Peruvian expression "

Incas si, Indios no", meaning, as Heaney puts it, "it is easy to romanticize the pre-Columbian past while ignoring the indigenous present".

After the US completed its conquest of the indigenous people within its own borders, it began its imperial march, beginning with Hawaii, and ending... well, we don't know, because it hasn't finished. While the country was fighting it out with Spain to re-colonize that country's colonies, jingoistic US pseudo-scientists were hot to prove that there had been advanced civilizations in the Americas before the Spanish conquest. Apparently the bitter irony was completely lost on them.

As for the Indian families already living in the ruins, Bingham dismissed them as "corngrowers [who] seemed to know little about the temples around which they had planted their crops. . . . They were of a different breed from the men who built the temples and had only dim traditions concerning them." . . . If Ishi and Peru's "corngrowers" were what Americans wanted to see in the indigenous present - nearly "extinct" hunters or "degenerated" and "dim" farmers - then the Incas and pre-Incas embodied the glorious pre-European past, whose proper heirs, the newspapers hinted, were the Americans who recognized them. The Christian Science Monitor simply and forcefully declared that Bingham's revelation left "the theory that civilization was first brought to these shores in Spanish caravels in a ridiculous light."

When the news of Bingham's "discovery" hit the press, it was an instant international sensation.

The story challenged racist beliefs that the Americas' indigenous peoples were incapable of building empires and settlements. By the same token, it fueled all sorts of wild and covertly racist theories — that the Incas were inspired by Egyptians, that they were Atlanteans or Asians — all implying that native Americans could not possibly have built an empire without external help. [Ed. note: Readers my age will recall similar nonsense about Peru's Nazca lines being built by space aliens.] . . .

Across the world, newspaper readers shook their heads at the wonder of it all. For Americans feeling regretful over the conquest of their own indigenous population, Machu Picchu offered a feeling of innocence and an almost imperial nostalgia for the pre-European past. It was easier to think of the noble, indigenous dead than the live Indians on and off reservations throughout the United States, fighting to protect native culture and treaty rights.

* * * *

As an aside, I was bemused to learn how far back the unethical corporate sponsorship of science dates. Heaney writes of the 1911 expedition:

The expedition's funding also hinted at its ethos. To cover everyone's food and travel expenses - each person needed $1,800 - Bingham collected $11,825, partly from businesses linked to America's frontiers, literal and imaginary. The Winchester Arms Company donated a rifle and $500. Minor C. Keith - whose all-powerful United Fruit Company owned railroads and plantations throughout Central America and would involve the US government in many a military imbroglio - put up $1,800 for another member and let the expedition travel on Untied Fruit's ships at half-fare. Finally, the Eastman Kodak Company donated cameras that Bingham promised to field test in Peru's rainy valleys.

Someone from the expedition crowed "that they were continuing 'the heroic work of the first explorers and founders like Pizarro.'" Again, no irony here.

And what of the "treasure"? What does Yale hoard? What was found at Machu Picchu, Ollantaytambo and other sites through the sacred Urubamba River valley? I wanted to know: what

didn't we see that should have been there?

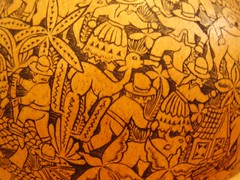

They found a bevy of complete or near-complete ceramic vessels, as well as the potsherds of 1,650 containers, ranging from tall liquid vessels to ornamented handles with the faces of animals and humans. . . . In the grave of one man, they found a pot filled with animal bones, grains, and other objects. . . . They found caches of intriguing green serpentine counters and a finely grained stone box, about six inches wide, eight-and-a-half inches long, and two-and-a-half inches deep, covered with beautiful angles and spirals.

They built an excellent collection of metallic objects. There was no gold — the Incas carried around such finery, and little of it survived the conquest — but they found "about two hundred little bronzes and a few pieces of silver and tin." They found large bronze knives, a silver headdress, and a moon-shaped silver headpiece.

In early September, Erdis pulled the expedition's most fabulous find from the northwest corner of one room: a "bronze knife, with handle decorated with figure of man with breech cloth, on stomach, feet in air, pulling on a rope, to which is attached a fish," he wrote in his journal. It was a truly unique piece, and the figure was beautifully detailed, with an Inca nose, earflaps on his hat, and a look of "grim determination" on his face. William Holmes of the Smithsonian would call it "one of the finest examples ever found in America of the ancient art of working in bronze."

The year's finest treasure, however, remained the tombs that Torvis Richarte and Anacleto Alvarez turned inside-out for the expedition, willingly or not. . . . That afternoon he and Richarte found a cave that yielded the ruin's second most delicate piece of metalwork: a small bronze pin with a tiny bronze hummingbird on top, a piece of string still threaded through its hole. They found a broken pot with a baby's skeleton at its bottom. A curious double burial would yield two skeletons, one with a stone and silver necklace still "at the neck of the dear departed," and, fascinatingly, a green glass bead — a European artifact, the first sign that the site was perhaps inhabited through the conquest. . . . When they were through, Richarte and Alvarez had opened 107 graves, yielding the remains of about 173 individuals. . . . There were no royal Inca mummies draped in gold, but as time went by, the Yale expedition realized they had found something even more important: a cross-section of the site's inhabitants, spanning the privileged "priestess" to the humble, malnourished worker. For those who knew how to read them, these bones were a treasure of a new sort, windows to their owner's past, gender, diet, and cause of death.

By collecting almost everything in the graves, no matter how modest, from humble metals to potsherds, Richarte and Alvarez let Yale make the first archaeological report in history on both the noble and common people of Inca society. Everything — from the skeletons to silver to stone carvings — went into 93 of the expedition's food boxes. [Ed note: that is, the boxes were not officially inventoried, they were falsely labelled and smuggled out of the country.]

Yale would ultimately list 5,415 lots of artifacts, but when counted in terms of individual bone fragments and potsherds, there were upwards of 46,000 pieces. It was a massive and invaluable array — priceless precisely because of its comprehensive nature. It was the only intact collection of human and artistic remains from an Inca royal estate that escaped the torches of the Spanish conquest. Put another way, Yale had now assumed the sacred trust of caring for Machu Picchu's tombs.

I believe that one day the Incan bones and other treasures now housed in Connecticut will be returned to Peru. If that happens in my lifetime, I may have to return to that country to see and celebrate them.